Introductory Note:

“Religion in our time has been captured by the tourist mindset,” writes Eugene Peterson in A Long Obedience in the Same Direction. What we need instead is the mindset of a pilgrim. The word pilgrim “tells us we are people who spend our lives going someplace, going to God.”

With the help of psalms recited by ancient Hebrew people making the pilgrimage ascent to Jerusalem, Peterson explores the contours of discipleship’s “long obedience.” In this excerpt, he examines what Psalm 121 has to say about our experience of hardship: “At no time is there the faintest suggestion that the life of faith exempts us from difficulties. What it promises is preservation from all the evil in them.”

Renovaré Team

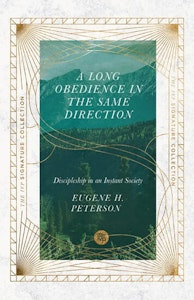

Excerpt from A Long Obedience in the Same Direction

Excerpt from A Long Obedience in the Same Direction

Not What We Had Expected

The moment we say no to the world and yes to God, all our problems are solved, all our questions answered, all our troubles over. Nothing can disturb the tranquility of the soul at peace with God. Nothing can interfere with the blessed assurance that all is well between me and my Savior. Nothing and no one can upset the enjoyable relationship that has been established by faith in Jesus Christ. We Christians are among that privileged company of persons who don’t have accidents, who don’t have arguments with our spouses, who aren’t misunderstood by our peers, whose children do not disobey us.

If any of those things should happen — a crushing doubt, a squall of anger, a desperate loneliness, an accident that puts us in the hospital, an argument that puts us in the doghouse, a rebellion that puts us on the defensive, a misunderstanding that puts us in the wrong — it is a sign that something is wrong with our relationship with God. We have, consciously or unconsciously, retracted our yes to God; and God, impatient with our fickle faith, has gone off to take care of someone more deserving of his attention.

Is that what you believe? If it is, I have some incredibly good news for you. You are wrong.

To be told we are wrong is sometimes an embarrassment, even a humiliation. We want to run and hide our heads in shame. But there are times when finding out we are wrong is sudden and immediate relief, and we can lift up our heads in hope. No longer do we have to keep doggedly trying to do something that isn’t working.

A few years ago I was in my backyard with my lawnmower tipped on its side. I was trying to get the blade off so I could sharpen it. I had my biggest wrench attached to the nut but couldn’t budge it. I got a four-foot length of pipe and slipped it over the wrench handle to give me leverage, and I leaned on that — still unsuccessfully. Next I took a large rock and banged on the pipe. By this time I was beginning to get emotionally involved with my lawnmower.

Then my neighbor walked over and said that he had a lawnmower like mine once and that, if he remembered correctly, the threads on the bolt went the other way. I reversed my exertions and, sure enough, the nut turned easily. I was glad to find out I was wrong. I was saved from frustration and failure. I would never have gotten the job done, no matter how hard I tried, doing it my way.

Psalm 121 is a quiet voice gently and kindly telling us that we are, perhaps, wrong in the way we are going about the Christian life, and then, very simply, showing us the right way.

But no sooner have we plunged, expectantly and enthusiastically, into the river of Christian faith than we get our noses full of water and come up coughing and choking. No sooner do we confidently stride out onto the road of faith than we trip on an obstruction and fall to the hard surface, bruising our knees and elbows. For many, the first great surprise of the Christian life is in the form of troubles we meet. Somehow it is not what we had supposed: we had expected something quite different; we had our minds set on Eden or on New Jerusalem. We are rudely awakened to something very different, and we look around for help, scanning the horizon for someone who will give us aid: “I look up to the mountains; does my strength come from mountains?”

Psalm 121 is the neighbor coming over and telling us that we are doing it the wrong way, looking in the wrong place for help. Psalm 121 is addressed to those of us who, “disregarding God, gaze to a distance all around them, and make long and devious circuits in quest of remedies to their troubles.”1

Help from the Hills?

A psalm that has enjoyed high regard among Christians so long must have truth in it that is verified in Christian living. Let’s return to the psalm: The person set on the way of faith gets into trouble, looks around for help (“I look up to the mountains”) and asks a question: “Does my strength come from mountains?” As this person of faith looks around at the hills for help, what is he, what is she, going to see?

Some magnificent scenery, for one thing. Is there anything more inspiring than a ridge of mountains silhouetted against the sky? Does any part of this earth promise more in terms of majesty and strength, of firmness and solidity, than the mountains? But a Hebrew would see something else.

During the time this psalm was written and sung, Palestine was overrun with popular pagan worship. Much of this religion was practiced on hilltops. Shrines were set up, groves of trees were planted, sacred prostitutes both male and female were provided; persons were lured to the shrines to engage in acts of worship that would enhance the fertility of the land, would make you feel good, would protect you from evil. There were nostrums, protections, spells and enchantments against all the perils of the road. Do you fear the sun’s heat? Go to the sun priest and pay for protection against the sun god. Are you fearful of the malign influence of moonlight? Go to the moon priestess and buy an amulet. Are you haunted by the demons that can use any pebble under your foot to trip you? Go to the shrine and learn the magic formula to ward off the mischief. Whence shall my help come? from Baal? from Asherah? from the sun priest? from the moon priestess?2

That is the kind of thing a Hebrew, set out on the way of faith twenty-five hundred years ago, would have seen on the hills. It is what disciples still see. A person of faith encounters trial or tribulation and cries out “Help!” We lift our eyes to the mountains, and offers of help, instant and numerous, appear. “Does my strength come from mountains?” No. “My strength comes from GOD, who made heaven, and earth, and mountains.”

A look to the hills for help ends in disappointment. For all their majesty and beauty, for all their quiet strength and firmness, they are finally just hills. And for all their promises of safety against the perils of the road, for all the allurements of their priests and priestesses, they are all, finally, lies.

And so Psalm 121 says no. It rejects a worship of nature, a religion of stars and flowers, a religion that makes the best of what it finds on the hills; instead it looks to the Lord who made heaven and earth. Help comes from the Creator, not from the creation.

The Creator is Lord over time: he “guards you when you leave and when you return,” your beginnings and your endings. He is with you when you set out on your way; he is still with you when you arrive at your destination. You don’t need to, in the meantime, get supplementary help from the sun or the moon. The Creator is Lord over all natural and supernatural forces: he made them. Sun, moon and rocks have no spiritual power.

They are not able to inflict evil upon us: we need not fear any supernatural assault from any of them. “GOD guards you from every evil.” The promise of the psalm — and both Hebrews and Christians have always read it this way — is not that we shall never stub our toes but that no injury, no illness, no accident, no distress will have evil power over us, that is, will be able to separate us from God’s purposes in us.

No literature is more realistic and honest in facing the harsh facts of life than the Bible. At no time is there the faintest suggestion that the life of faith exempts us from difficulties. What it promises is preservation from all the evil in them. On every page of the Bible there is recognition that faith encounters troubles.

The sixth petition in the Lord’s Prayer is “Lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil.” That prayer is answered every day, sometimes many times a day, in the lives of those who walk in the way of faith. St. Paul wrote, “No test or temptation that comes your way is beyond the course of what others have had to face. All you need to remember is that God will never let you down; he’ll never let you be pushed past your limit; he’ll always be there to help you come through it” (1 Cor 10:13).

One God, One Gospel

The great danger of Christian discipleship is that we should have two religions: a glorious, biblical Sunday gospel that sets us free from the world, that in the cross and resurrection of Christ makes eternity alive in us, a magnificent gospel of Genesis and Romans and Revelation; and, then, an everyday religion that we make do with during the week between the time of leaving the world and arriving in heaven.

We save the Sunday gospel for the big crises of existence. For the mundane trivialities — the times when our foot slips on a loose stone, or the heat of the sun gets too much for us, or the influence of the moon gets us down — we use the everyday religion of the Reader’s Digest reprint, advice from a friend, an Ann Landers column, the huckstered wisdom of a talk-show celebrity. We practice patent-medicine religion.

We know that God created the universe and has accomplished our eternal salvation. But we can’t believe that he condescends to watch the soap opera of our daily trials and tribulations; so we purchase our own remedies for that. To ask him to deal with what troubles us each day is like asking a famous surgeon to put iodine on a scratch.

But Psalm 121 says that the same faith that works in the big things works in the little things. The God of Genesis 1 who brought light out of darkness is also the God of this day who guards you from every evil.

- John Calvin, Commentary on the Psalms (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Eerdmans, 1949), 5:63. ↩︎

- Johannes Pedersen describes the situation thus: “The sun and the moon, which meant so much for the maintenance of order in life, often became independent gods among the neighboring peoples or became part of the nature of other gods. Job expressly denies having kissed his hand to these mighty beings (‘ … if I have looked at the sun when it shone, or the moon moving in splendor, and my heart has been secretly enticed, and my mouth has kissed my hand; this also would be an iniquity to be punished by the judgment, for I should have been false to God above’). And in a judgment prophecy it is said that Yahweh will visit all the host of heaven on high, and the kings on earth, and the sun and the moon shall be put to shame, when Yahweh shall reign in Zion (‘Then the moon shall be confounded and the sun ashamed; for the Lord of hosts will reign on Mount Zion and in Jerusalem.’ Isaiah 24:33).” Israel: Its Life and Culture (London: Oxford University Press, 1926), p. 635. ↩︎

Taken from A Long Obedience in the Same Direction by Eugene Peterson. Copyright © 2000 by Eugene Peterson. Published by InterVarsity Press, Downers Grove, IL. www.ivpress.com

Art: Landscape of the Moon’s First Quarter, 1943 by Paul Nash (d. 1946), shared via Birmingham Museums Trust on Unsplash

Text First Published June 1980 · Last Featured on Renovare.org January 2022