Introductory Note:

Carol Berry has been studying Vincent van Gogh since she first took a course on the artist in 1979, under the instruction of Henri J.M. Nouwen. Carol’s recent book describes all that she learned from Henri about Vincent, as well as the insight into his life that she gained by retracing van Gogh’s movements through the towns and villages where he lived and worked in the Netherlands, Belgium, and France. In the excerpt below, Carol recalls how Henri helped his students to see Vincent’s intentional residence in “unpopular places” and his solidarity with suffering people as a model of Christlike consolation.

Renovaré Team

Excerpt from Learning from Henri Nouwen and Vincent van Gogh

Excerpt from Learning from Henri Nouwen and Vincent van Gogh

We were by now partway through our course with Henri, and we had yet to meet Vincent the artist. Henri had wanted us to spend a considerable amount of time with Vincent in the cold, dark place of the Borinage where Vincent committed to his deep solidarity with a suffering humanity. In the direct confrontations with the plight of the miners and having nothing left to give but himself, his solidarity helped him to discover his own inner spark; it transformed him.

Enriched with the understanding that he was an integral part of a suffering humanity, he realized that his personal call to a life of compassion would be fulfilled as an artist. And Vincent discovered that what had nurtured him since childhood — the biblical parables, art, stories, and the closeness to nature — would guide him in his true vocation.

Henri stressed that to become compassionate people, we had to recognize and admit “our intimate solidarity with the human condition.”1 We had to give up our desire to be different, exceptional, or better than the others in order to become a consoling presence.

Consolation demands that we be cum solus with [alone with] the lonely other, and with him or her exactly there where he or she is lonely and where he or she hurts and nowhere else. Consolation is … not the avoidance of pain, but, paradoxically, the deepening of a pain to a level where it can be shared.2

This was a hard concept to grasp and Henri knew that. And here we could see why Henri had chosen Vincent van Gogh as his case study. Through Vincent’s story, through the parable of his life, we were to come closer to an understanding of what it meant to be a consoling presence.

After leaving the Borinage, Vincent consciously made the choice to stay close to the suffering of others. He kept going to unpopular places to draw and paint people who most others did not consider worth paying attention to, reminding us that this was living according to the example of Jesus.

Emerging from his isolation and time of transformation in the Borinage, Vincent moved back with his parents, who now lived in the small Brabant parish of Etten. Having a place to live for a while enabled Vincent to devote himself entirely to practicing the skills he needed in order to express graphically what he saw and felt. He lived close to the people he drew and felt their existence from within his own experience.

Continuing on his path to unpopular places, […] he moved to a poor district of The Hague, where he invited one of his models, Sien, to live with him. She was a poor, worn-out prostitute who had a young child and was pregnant with another. He cared for her and her child, and gave her a safe place to stay while she awaited the delivery of her second child.

The commitment Vincent made to Sien would make him share what meager resources he had and therefore sacrifice his own comfort and well-being. Vincent endured his own suffering and Sien’s destitution together with her, and this was, according to Henri, a most moving portrait of consolation.

Henri elaborated,

When we say to a suffering person, “don’t cry” or “things will be better tomorrow” or “don’t worry,” we really try to move that person to a place where he or she is not. But to console means first of all to be with someone where it hurts. And that’s not very easy because how can you be with someone who hurts if you don’t want to be here with your own pain. And therefore we run away from the pain instead of deepening it. We want to avoid it and cover it up.3

Henri urged against the avoidance of pain. He was rather warning people to be more human, and pain is part of that, just as is joy. Henri emphatically added, “To say that I too am in pain, that I too am part of that human condition, that’s a very hard thing to say and to feel. And still that’s what I think consolation is.”4

Vincent installed himself in a studio that became, as he saw it, a shelter for the poor who came to model for him. Being as poor as they were, he identified with their wounds of life and would rather go without a meal himself than not pay them a modest few coins for their modeling.

One of the images Henri wanted us to spend a considerable amount of time with was a drawing of Sien called Sorrow. Vincent, as expressed to Theo in one of his letters, could not have created this expressive image if he hadn’t felt this kind of sorrow himself. He had spent time cum solus with Sien and her children and without pretense entered into their pain. By feeling the wounds of her life, he understood her predicament and became a consoling presence.

Accepting and even welcoming the risk of his own discomfort and alienation from his family, he wrote to Theo: If “for a moment I may feel rising within me the desire for a care-free life, for success — each time I go fondly back to the trouble, the cares, to a difficult life — and think, it is better this way, I learn more from it; it does not debase me. It is not on this road one perishes.”5

Henri concluded his talks about consolation with these words,

No one wants to increase his or her own pain, but rather invite the hurting person to come to a place, our own place, where the pain is less. For going down into the deep pain of another is like jumping into a bottomless abyss — not knowing if or where one will land. To grasp another’s pain means letting go of our own safety limb and falling down to an unknown place. In this place we maybe won’t have the answers that will help or alleviate the pain or explain it. We have to be willing to admit, then and there, down in the pit, that we too are helpless and weak and powerless. And who wants to do that, or be there?6

Vincent did that and was there with Sien and the people of the almshouses and soup kitchens.

Vincent did not have the answers for Sien. But by treating her with tenderness and esteem, he believed he could change her own perception of herself.

We began to understand. Not only would we not have the answers, but also it was precisely when we stopped looking for answers that we could become an unconditional consoling presence. The paradox of not offering advice in a situation where the need of it was perceived was almost unfathomable, but Henri kept reassuring us that this was getting closer to the dynamics of compassion. When we were willing, through a shared vulnerability, to admit that we were not coming to the hurting person from a place of superiority but were on equal footing, then we could begin to console.

Related Podcast

- Henri J. M. Nouwen, “Compassion: Solidarity, Consolation and Comfort,” America, March 13, 1976. ↩︎

- Nouwen, “Compassion.” ↩︎

- Henri Nouwen, “The Compassion of Vincent van Gogh” (lecture, Yale University, New Haven, CT, 1978), audiotape. ↩︎

- Nouwen, “The Compassion of Vincent van Gogh.” ↩︎

- Letter to Theo, The Hague, May 12 or 13, 1882. ↩︎

- Nouwen, “Compassion.” ↩︎

Adapted from Learning from Henri Nouwen and Vincent van Gogh by Carol Berry. Copyright © 2019 by Carol Berry. Published by InterVarsity Press, Downers Grove, IL. www.ivpress.com

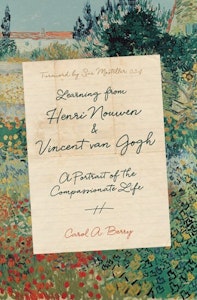

Art: Vincent van Gogh. Women carrying coal sacks in the snow, November 1882. Brush and ink. 32.1×50.1 cm. Kröller-Müller Museum.

Text First Published May 2019 · Last Featured on Renovare.org January 2022