Last week I mentioned that the expression “image of God” is a phrase that is given maddeningly little formal definition in Scripture. This is correct — except that when we examine the New Testament testimony, the Christological and incarnational focus of the “image of God” is striking. Let’s take a closer look.

Paul writes to the Corinthian Christians about “the glory of Christ, who is the image of God” (2 Cor. 4:4), and he tells the Colossians that it is Christ who “is the image of the invisible God, the firstborn over all creation” (Col. 1:15). Christ, the image of God, is the Word made flesh (John 1:14), “the only begotten God who is in the bosom of the Father” (John 1:18), the eternal Son who has created all things (Col. 1:16). The Letter to the Hebrews states that the Son “is the radiance of God’s glory and the exact representation of his being, sustaining all things by his powerful word” (Heb. 1:3).

So, though the New Testament does not define what “image of God” means, when this phrase is used we are directed to Jesus Christ. To look closely at Jesus is to see at last what a real human being looks like.

This untarnished image of God, who represents God so perfectly that whoever has seen him “has seen the Father” (John 14:9), has come into the world to redeem us. And how has this redemption been accomplished? In this year’s Renovaré Book Club, we will be reading Athanasius’s On the Incarnation. As a preview of coming attractions consider how Athanasius explains Christ’s redeeming work:

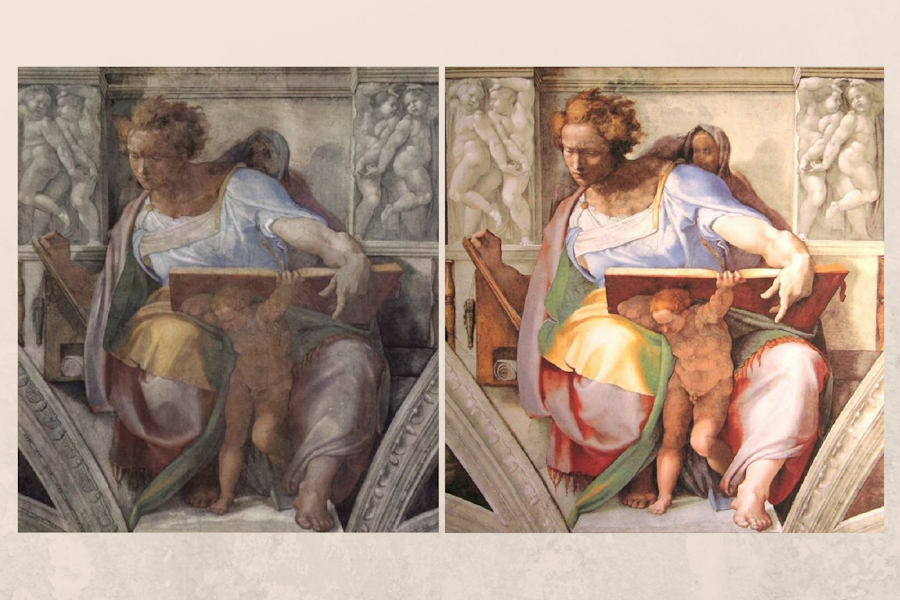

“You know what happens when a portrait that has been painted on a panel becomes obliterated through external stains. The artist does not throw away the panel, but the subject of the panel has to come and sit for it again, and then the likeness is re-drawn on the same material. Even so was it with the All-holy Son of God. He, the image of the Father, came and dwelt in our midst, in order that He might renew mankind made after Himself.”

Athanasius’s metaphor is beautiful. If the seriousness of sin forbids a solution that is merely external and therefore superficial, here is a powerful account of the eternal Word taking on human nature precisely in order to make it new from the inside out. Other ancient Christian writers formulate this idea pithily in in terms of the famous principle, “Whatever is not assumed is not healed” — in other words, our diseased human nature is “healed” only when every aspect of it is taken on (“assumed”) by God the Son and is thereby united with the intensely personal Trinity. Then, when our lifeless nature is connected to the Source of infinite life, it is regenerated, raised, re-created, renewed, restored. It becomes again what it was meant to be, a genuine, authentic image of the living God, ready once again to know God himself.

Whatever was broken in the created image of God has now been restored by the incarnation of the eternal image of God. Human nature is remade, as God the Son united it to himself in order to make it new from the inside out (2 Cor. 5:17); our ignorance is overcome, as he lives a perfect life in order to show us what real humanity is (Heb. 4:15); our guilt is atoned for, as he dies a sinner’s death in order to cancel forever the charge that is against us (Col. 2:13 – 14); our corruption is healed, as he rises to life again in order to inaugurate a new humanity with a new nature for a new age, that all who are in Christ may walk in newness of life (Rom. 6:4). As if all this achievement of Christ were not enough, God the Spirit also is given, to inscribe the law on believers’ hearts (Heb. 10:15 – 16), to work inside us to draw us into the newness, the fullness, that is ours in Christ (John 16:13 – 15). Salvation is nothing less than full entrance into the life of Jesus by the Spirit.

Catch up with all of Chris’s installments in the Mystery of God series at Conversations with Chris.

This series has been adapted from Steven D. Boyer and Chris Hall’s The Mystery of God: Theology for Knowing the Unknowable. Hungry for more? Please visit Baker Academic for more information.

PC: By Webgallery of Art, Bartz and Konig, “Michelangelo”, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons.