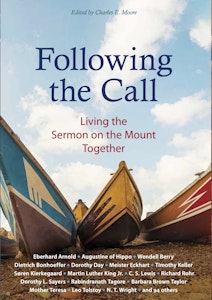

Excerpt from Following the Call

Excerpt from Following the Call

“When Christ calls a man, he bids him come and die.” These unforgettable words of the German martyr Dietrich Bonhoeffer express a fundamental truth: when Jesus calls us, our old life comes to an end and something new begins. That something, however, is not necessarily what we expect or what we want. Jesus’ message is as unsettling as it is clear: “If anyone would come after me, he must deny himself and take up his cross daily and follow me.” What does this entail? What does it mean to hear Jesus’ voice and follow him?

There is no better place to start than to hear what Jesus says in the Sermon on the Mount. It is, as Harvey Cox states, “the most luminous, most quoted, most analyzed, most contested, and most influential moral and religious discourse in all of human history.” The Sermon on the Mount includes many of the best-known scriptures in the Bible. Who isn’t familiar with the Beatitudes? The Lord’s Prayer? The Golden Rule? The command to love one’s enemy? Or such vivid expressions as “Ask and it will be given to you, seek and you will find”?

The Sermon on the Mount possesses an irresistible, compelling quality. At the same time, who hasn’t felt uneasy after reading Jesus’ words? “By all means,” Gandhi once wrote, “drink deep of the fountains that are given to you in the Sermon on the Mount, but then you will have to take sackcloth and ashes.” Perhaps this is why Walter Kaufmann argues that Christianity is simply “the ever renewed effort to get around these sayings without repudiating Jesus.” But the Sermon on the Mount is all but impossible to ignore. Jesus’ words get to the root of the human condition. This is one reason why so much ink has been spilt over it, and why this collection exists.

This collection is unique in several respects. First, it consists of a range of voices from various traditions and time periods. In this way one can glean wisdom from outside one’s own tradition. Second, this book is neither a commentary nor a devotional. Its thrust is prophetic, propelling readers toward putting Jesus’ teachings into practice in their lives. Finally, this book is designed to be read slowly and carefully with others. The selections have been chosen to engage and inspire communities of faith. Toward that end there is a discussion guide at the back with reflection questions for each chapter. Jesus spoke to his disciples collectively, often responding to their questions. His aim was to form a band of followers who would put into practice what he said, and he painted a picture for them of such a community. Like the prophets, Jesus cast a vision of the coming age and exhorted his disciples to order their lives around its virtues.

The picture Jesus paints of God’s kingdom community comes in the form of one long teaching, which has pride of place as the first of five major teaching discourses in the Gospel of Matthew. Matthew 5 – 7 is more than a collection of miscellaneous sayings. Though Jesus may not have delivered this sermon word for word in one sitting, it is the kind of talk he gave to those who had dropped everything to follow him and were wondering, “What next?”

In broad strokes, the Sermon consists of three sections. The first (5:3 – 16) comprises blessings and details the character of citizens of God’s kingdom. The overarching theme of the second section (5:17 – 7:12) is the greater righteousness of the kingdom in relation to the Law of Moses, whether the subject is religious devotion or various social obligations. The Sermon is then rounded off by an epilogue (7:13 – 27) with warnings and a challenge to put these words into practice.

One thing that stands out throughout the Sermon is Jesus’ use of language and images. The Sermon is masterfully poetical and also richly pictorial. Jesus refers to salt, light, a city on a hill, a splinter and a plank, two kinds of gates and two kinds of houses. He describes ordinary people and everyday life: a beggar on the roadside, a Roman official, a pious Pharisee, a local builder, a thief, a judge. The sights and sounds of nature — sun and rain, wind and flood, thistle and thorn, vine and figs, birds and moths, dogs and swine, sheep and wolves — help us visualize what life in the kingdom is like. Finally, Jesus’ style is proverbial. He expresses truths and principles in a simple yet provocative way, often using vivid, hyperbolical language. He doesn’t mean for us to literally cut off one of our hands if it causes us to sin, but he makes his point and uses startling language to ram it home.

The pictures and examples Jesus gives not only cast a vision of God’s new kingdom of righteousness, peace, and love; they compel us to respond. When reading the Sermon on the Mount we can’t just nod our heads. Jesus aims to jolt his listeners into a new frame of reference, a vision of life that radically alters everything. His followers have not always remembered this, falling into arguments over what he meant and diluting what he said with qualifying commentary.

During different periods of church history, the pendulum has swung back and forth between the belief that Jesus’ teachings are fully realizable and the view that they are conditional and only partially realizable.

Are Jesus’ teachings realistic, or possible to achieve, or relevant for today? How far can they be applied? What does it mean to live them out — personally, interpersonally, in various spheres of life and society? If we cannot take literally everything Jesus says, then is it better to just understand his words figuratively? Did Jesus bring a new law, more radical and far-reaching than the old, or was his focus mostly on the condition of the heart?

Part of the problem is that we live in the tension between two poles: the new order that God wants to bring about, which becomes possible in Christ, and the existing fallen order, of which we are still a part. All the more we should strive to grasp Jesus’ original intention. The approach taken here views the Sermon on the Mount in terms of what life in the kingdom of God is like among those who have heeded the call to discipleship. Jesus intended his followers to put his words into practice individually and together, bearing witness to the in-breaking of his kingly rule here and now. The following three motifs, embedded in the Sermon itself, bear this out.

The Kingdom of God

The horizon and goal of the Sermon on the Mount is the kingdom of God — wholehearted, total, single devotion to the rulership of God. In Jesus’ teachings, God’s kingdom is not a place but the revolutionary effect of God reigning among his people here on earth. This kingdom is not an ethic or an ideal. Rather, it is a reality in which God’s future breaks into our midst.

Jesus’ words about a kingdom were inflammatory. One need only remember his execution and the reason given: “This is Jesus the King of the Jews.” Announcing the arrival of another kingdom in a province governed by Rome was daring and provocative. There existed only one recognized political authority. The Romans tolerated no contender and were quick to squelch any rebellion or would-be messiah who might restore independence to the Jewish people.

Jesus’ message also upended some of the Jews’ expectations of who the Messiah would be and what he would do. In Jesus’ kingdom, the poor and slaves are given dignity and all who pledge themselves to Jesus are brothers and sisters. It doesn’t look much like a kingdom. It comes into being internally, hidden from sight in the lives of individuals. From there it flows out to others, binding them in relationship, but does not rest on power structures or any kind of top-down organization.

Jesus’ message was more than a prophetic indictment of the existing order. It was ultimately good news. Matthew places accounts of Jesus’ miracles right before and right after the Sermon. Jesus’ words regarding God’s reign are spoken against the backdrop of his works of healing. His commands belong to his gifts. The one who preached repentance is also the one through whom the power of evil and sin is broken. Jesus thus launches a new movement that both threatens and promises to change everything. His message is one of liberation, not so much from an empire or a religious system as from the bonds of sin, power, injustice, and death that give rise to exploitation and dehumanization.

A Contrast Community

The Sermon on the Mount is neither an ethic for society in general nor an ideal of perfection for the individual. It makes no sense to view it as a universal code or pattern for all people to live by. When separated from Jesus, his teachings float in midair and can mean virtually anything. As Albert Schweitzer warns, expounding Jesus’ words as though they were bound to win universal acceptance “is like trying to paint a wet wall with pretty colors. We first have to create a foundation for the understanding.” Granted, the crowds were free to listen, but Jesus’ focus was on his disciples. As John Stott writes in his book Christian Counter-Culture:

The standards of the Sermon are neither readily attainable by every man, nor totally unattainable by any man. To put them beyond anybody’s reach is to ignore the purpose of Christ’s Sermon; to put them within everybody’s is to ignore the reality of man’s sin. They are attainable all right, but only by those who have experienced the new birth “Make the tree good, and its fruit will be good.”

Jesus came to gather those who are ready to leave their old lives to join him on a new path. That he aims his remarks specifically at his disciples is shown by the fact that he calls them, in particular, “salt and light.” His followers are different. They love their enemies, pray simply, give generously, and don’t judge others. They know their need for God and are prepared to suffer for Jesus’ sake.

These disciples, however, are not just a bunch of individuals. They are different because Jesus forms them into a distinct community. Plural pronouns are used throughout the Sermon on the Mount. The Lord’s Prayer, for example, is a communal prayer, not a personal one. Jesus’ warnings against wealth and worry presuppose practices of radical sharing, and his instructions about genuine worship presume unhindered brotherly and sisterly fellowship. When Jesus calls people to himself, a new kind of community is born. Life in God’s kingdom means being a certain kind of people together. That is the essential mark and purpose of the church. The church’s witness is the communal embodiment of the Sermon. It therefore serves as a contrast to society and does so by practicing righteousness and justice in every relationship and deed. Such a social witness is never established with the force of arms or won at the expense of bloodshed. Instead, Jesus gets at the root of what oppresses each person and what divides society in general. He confronts the destructive forces that break apart human relations: pride, anger, lust, envy, falsehood, retaliation, judgment, and unforgiveness. More importantly, he provides the antidote to these: a lowly way of love that leads to peace.

Jesus’ disciples make up, in the words of the apostle Paul, a “new humanity,” which includes people who by the world’s standards should be mutually antagonistic but who are now reconciled and belong to one another (Eph. 2:11 – 22). Jews and Gentiles, for example, become comrades in a life together in which God’s justice and peace are realized. This truly revolutionary order is the context in which to comprehend and live out the Sermon on the Mount.

A New Possibility

God’s new order, however, is not some kind of alternative social blueprint. The Sermon on the Mount is not an ideology. Jesus’ message must be understood in the light of who he is and why he came. Jesus himself is the in-breaking of God’s kingdom in person. As God’s anointed one, he is the king of the kingdom. Jesus himself is the content of his sayings. He is not only the master teacher and the best example of his own teaching, he demonstrates in his life the very presence and power of God’s future. Jesus’ every imperative — “Turn the other cheek,” “Love your enemy,” and so forth — is rooted in his spirit-filled life. In heeding his call, his followers are empowered by the same spirit to live out a new possibility.

That new possibility involves matters of the heart as well as the actions that follow. It is within the individual human heart that the transformation begins. And yet deeds always follow. Indeed, Jesus placed great emphasis on doing his word. Living out his commands and the state of one’s heart go hand in hand. Jesus does not separate the outer and inner, the personal and social. He is always concerned with the whole person.

Does this mean we can fully implement the Sermon on the Mount? Yes, if we understand it against the horizon of God’s grace and his reign. No, if we treat it as some kind of ethic we are obliged to live up to. The moment Jesus’ words are severed from his healing and invigorating power, they lose their true significance. As Eberhard Arnold reminds us, the Sermon on the Mount “is not a high-tension moralism” but rather “the revelation of God’s real power in human life. It is like a flame that shines, like the sap that pulses through a tree. It is life.” Jesus does not impose intolerable demands on us. “If we take our surrender to God seriously,” Arnold goes on, “and allow him to enter our lives as light, as the only energy which makes new life possible, then we will be able to live the new life.” Those who respond to Christ’s call and willingly place themselves under his lordship will find in the Sermon on the Mount a priceless treasure full of wisdom, guidance, and assurance.

Though hard on the flesh, Jesus’ words capture the qualities, actions, and attitudes of the citizens of God’s new order. If a Roman soldier forces them to carry his pack one mile, they carry it two miles. Jesus calls us to turn every such situation around. Who knows what might happen? God’s peace might just be advanced on earth.

The Sermon on the Mount can be as daunting as it is appealing, exciting but also sobering. In reading the following selections, we must remember that Jesus did not come to impose anything on us; he came to redeem, not condemn!

Jesus does not call us to some “impossible possibility.” No, he gives witness to the fact that God is able to meet our deepest longings for righteousness, mercy, peace, and love. Yes, Jesus calls us to pick up our cross daily, but in doing so we find life. “It is enough,” Jesus says, “for the disciple to be like the teacher.” By hearing Christ’s call in his teaching, and then doing what he says in the strength of the promised Spirit, we will find our lives resting on solid rock and receive a foretaste of even greater things to come.

Excerpted from Following the Call: Living the Sermon on the Mount Together, published 2021 by Plough Publishing. Used with permission.

Text First Published September 2021 · Last Featured on Renovare.org September 2021