Introductory Note:

Randy Schrock courageously shares how God delivered him from a sense of worthlessness and shame. His raw and touching narrative includes some heavy topics—emotional abuse, pornography, and suicide. It is a powerful reminder that God’s salvation encompasses all types of brokenness and woundedness, and it is encouraging to know that we can join God in this work. From his own experience, Randy distills four principles for practicing hospitality towards the wounded, rejected, and isolated in our own unique settings.

Renovaré Team

When I entered high school at fourteen, I was lost, awkward, and painfully shy. My personal and social disorientation was more than the average adolescent identity crisis. My concern was not where or with whom I belonged, but rather if I belonged at all. I questioned my value as a human being.

This unfavorable self-assessment had several sources. In part, my shame developed from being immersed in the cesspool of pornography from an early age. I experienced a sense of personal degradation because these images possessed such a powerful hold on my young mind.

A more significant catalyst for my bleak self-appraisal was my father. It was he who facilitated my exposure to sexually explicit materials as he left them scattered around the house. His influence did not end there. He directly attacked my sense of worth with a constant barrage of demeaning remarks. He belittled me. He rejected my best efforts and disdained my accomplishments. The anxiety of never being able to meet my father’s expectations filled me with self-doubt and left me feeling incompetent. His tendency to become angry with little provocation left me timid.

Years of derision and discouragement left an indelible imprint. My dad’s assessment became deeply embedded in my mind, my heart, and my soul until I considered myself worthless. While I never considered suicide, I have met several young people over the years whose similar self-assessments led them to such thoughts. They just want to escape the pain or relieve others of the burden they perceive themselves to be.

I was rejected by my father, ignored by peers, and, I assumed, loathsome to God. How could anyone value someone as pathetic as me? I was confused in multiple ways, but at the core was this spiritual alienation. All aspects of my internal chaos arose out of this fundamental reality. This is why I came into high school so lost.

But there was a small light at the end of the tunnel, a dream that God would use to help me discover my value and belovedness.

I might have been inept in human relationships but I connected well with animals. So I dreamed of becoming a veterinarian. I expressed this vision to my guidance counselor who assigned me to take biology with one of the best teachers at that high school, Mr. Rasmussen.

In the end, I would not become a veterinarian, but pursuing this goal opened the door to a life-changing relationship. I met a man who valued me. In the many hours after school that we spent together cleaning his classroom, tending the lab animals, and talking about science, Mr. Rasmussen cared enough to get to know me.

What did Mr. Rasmussen offer me? He spoke words of encouragement, yet he was not a counselor and never tried to provide therapy. He maintained good boundaries. I was his student, not his friend. And he was my teacher, not a substitute father figure. He simply made a connection which somewhat alleviated my sense of worthlessness. He accomplished this by being a good host — he made space for me in his lab and his life and helped me to feel comfortable in his presence. Mr. Rasmussen offered me hospitality. This was a transformative gift.

By God’s grace, over time, I was substantially delivered from my struggles. As painful as my journey was, it has proved invaluable in my work with wounded, neglected, and abandoned children and teenagers. For more than twenty years I have had the privilege of working with this population, which sadly is ever-increasing.

I’ve learned that hospitality is a crucial aspect of the compassionate life of Jesus — a life he invites us to imitate. We are called to love our neighbors. Fulfilling this calling requires us to give not just our resources but our very selves to those in need. Paul commends the hospitality of the Macedonian churches, because “they exceeded our expectations: They gave themselves first of all to the Lord, and then by the will of God also to us” (2 Corinthians 8:5 NIV).

How can we give ourselves to the least, the lost, and the lonely, as Mr. Rasmussen offered himself to me? My experience with troubled young people has taught me that Christlike hospitality embodies the following four commitments:

1. Gentle Persistence

Children or adults who have been ignored, mistreated, and rejected will likely be suspicious of our efforts to offer ourselves to them. This is to be expected.

We must not be put off by their mistrustful responses, unpleasant attitudes, or poor behavior. They may test us or deliberately incite us to reject them. At any time, they can choose to walk away, but, for our part, we must commit to unconditionally leaving the invitation open.1 We offer gentleness and persistence in our hospitality. This allows wounded people to feel safe lowering their defensive walls and opens the way for emotional, physical, and spiritual transformation through healthy interactions.

2. Unconditional Acceptance

The writer of Hebrews reminds us: “Do not neglect to show hospitality to strangers…” (Hebrews 13:2). The strangest guests we may ever host are those I describe as the least, lost, and lonely. These wounded and troubled people will not always be easy to tolerate. They may be dirty and disheveled and profane. And yet, we must recognize “true hospitality is welcoming the stranger on her own terms…” (Nouwen, Reaching Out, 72). This means that we accept the person as they are and as a human being, not as we want them to be or as a “project.” We forgo ulterior motives (which they can detect). Certainly, we desire their healing and transformation, but we follow Jesus’ example and love people whether or not they make progress. Henri Nouwen clarifies, the purpose of “hospitality is not to change people, but to offer them space where change can take place” (Nouwen, Reaching Out, 71).

3. Vicarious Suffering

Accepting people on their own terms includes receiving the individual along with their woundedness. They come to us lonely, abandoned, and traumatized, and our hospitality should encompass their grief and pain. Offering hospitality to wounded people means that we enter into their suffering. We “mourn with those who mourn” (Romans 12:15).

Madeleine L’ Engle writes, “Compassion means to be with, to share, to overlap (with the other) no matter how difficult or painful it might be. And compassion is indeed painful…” (L’Engle, Genesis Trilogy, 69).

This empathetic process is beautifully illustrated by Walter Wangerin in his short story “Ragman.” A Christlike figure goes from one wounded person to another collecting their rags and offering them clean linen and healing. In one scenario, he takes the soiled handkerchief of a sobbing young woman, holds it up to his own eyes, and begins weeping her tears (Wangerin, Ragman, 4). The theological term for this is vicarious suffering. While we are not Christ and cannot fully assume another’s pain, as Christ’s representatives we are called to be with those who suffer and share their tears.

4. A Seed-Sowing Perspective

Like Paul and Apollos, we plant and water (1 Corinthians 3:6). We pray that our care, persistence, patience, and acceptance will sow seeds that help lost people discover their identity as God’s beloved. But we must remember that, as Paul declares, it is God who gives the growth. In offering hospitality, it is important for us to forego expectations as to when and what type of change will occur. We pray and trust God to produce growth in his time.

Mr. Rasmussen created a safe space for me. He accepted me as I was. He was compassionate and persistent. His attentive care provided evidence that I possessed value and worth. His hospitality planted a seed that challenged the negative self-image holding me captive. This seed, though, would not bear fruit until I left high school.

It took many years to recognize the significance of Mr. Rasmussen’s influence on my healing. In this life, he never knew his impact on me. Likewise, we may never know the impact we make on one of these least, lost, and lonely people. But God does.

L’ Engle, Madeleine. The Genesis Trilogy. Waterbrook Press, Colorado Springs, Co, 1997.

Nouwen, Henri J. M. Reaching Out: The Three Movements of the Spiritual Life. Image, New York, 1975.

Wangerin, Walter, Jr. Ragman and Other Stories of Faith. HarperCollins, New York, 1994.

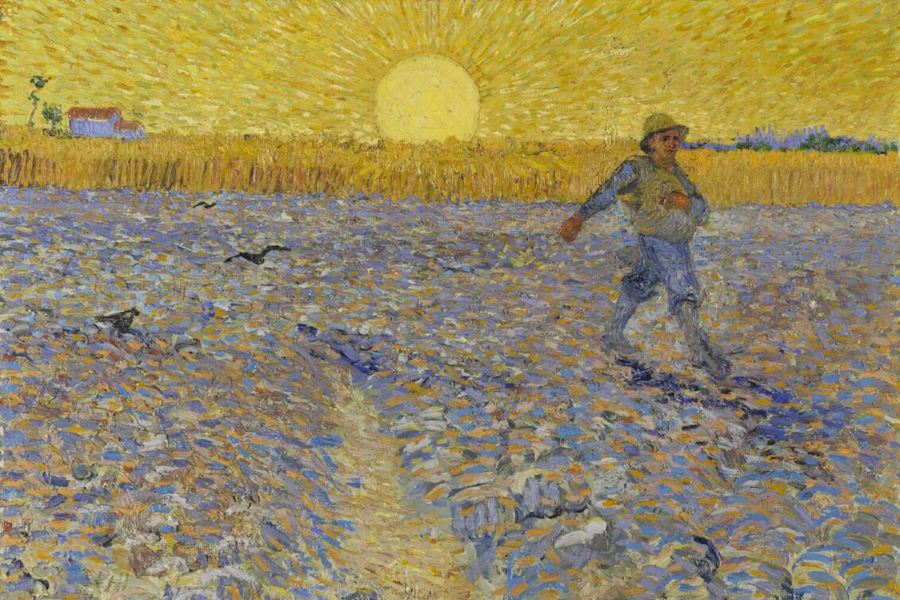

Art: Vincent van Gogh. The Sower, circa June 17 – 28, 1888. Oil on canvas, 64.2 x 80.3 cm. Kröller-Müller Museum.

Text First Published January 2022 · Last Featured on Renovare.org January 2022