Jesus describes himself as “the bread of life … the bread that comes down from heaven, which one may eat and not die. I am the living bread that came down from heaven. If anyone eats of this bread, he will live forever. This bread is my flesh, which I give for the life of the world … I tell you the truth, unless you eat the flesh of the Son of Man and drink his blood, you have no life in you. Whoever eats my flesh and drinks my blood has eternal life, and I will raise him up at the last day. For my flesh is real food and my blood is real drink” (John 6:48 – 55).

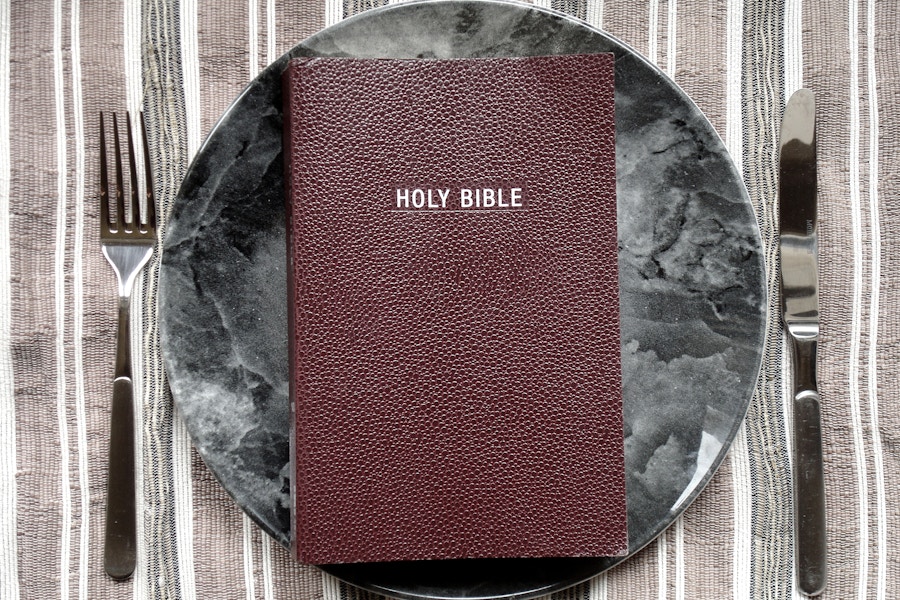

While the church has often interpreted Jesus’ words as supporting an elevated, realistic view of the Eucharist, these texts also provide the theological rationale for devouring the Scripture, for gnawing on it like a dog chewing on his bone. For the Scriptures speak of Christ, from beginning to end. Think of the experience of the disciples on the road to Emmaus. Jesus scolds them for failing to understand the Scripture and how the texts they had studied for much of their lives pointed to him.

“How foolish you are, and how slow of heart to believe all that the prophets have spoken! Did not the Christ have to suffer these things and then enter his glory? And beginning with Moses and all the Prophets, he explained to them what was said in all the Scriptures concerning himself (Luke 24:25 – 27). It is when Jesus breaks bread with these disciples that their eyes are opened (Luke 24:31). What had been their problem thus far? They had been “slow of heart to believe” (Luke 24:25).

Jesus is insistent. He reiterates the point he made on the road to Emmaus when he appears to the disciples, perhaps within hours, again in a context of eating and fellowship: “They gave him a piece of broiled fish, and he took it and ate it in their presence. He said to them, ‘This is what I told you while I was still with you: Everything must be fulfilled that is written about me in the Law of Moses, the Prophets and the Psalms’” (Luke 24:42 – 44).

To meditate upon the Scripture — a key aspect of lectio divina—involves more than simply reading it. Meditatio is a slow, paced, leisurely gnawing on the Scripture, a reading that breaks through the bone and sucks out the marrow, Christ himself. Meditatio is a Christological munching, an eschatological feeding because the food offered to us is grown and harvested in the fields of the age to come, assimilating Jesus, as Peterson puts it, metabolizing him in a concrete, earthy fashion so that he becomes what we are and in so doing changes us into himself.

To stay with the direction of the metaphor, we can see how this kind of eating will likely be a slow-paced, delight-filled affair. Cracking the bone will take some time. We will need to be patient, with the text and with ourselves. As far as the text is concerned, we all know that certain biblical texts are accessible, delightful, and readily feed us. There is little bone to crack, for instance, in Psalm 23. Other texts are less accessible, bony, resistant to our gnawing, well-nigh indigestible. “Why would the Holy Spirit want me to know this?” we ask. How, in any discernible way, is Christ present here?

We don’t desert exegesis at this point, letting our imaginations run wild in a search for spiritual insight. Rather, exegesis helps us to crack open the text. Or, to develop the metaphor, solid exegesis is a textual nutcracker. Yet if we simply exegete the text — analyzing it in terms of its syntax, historical, and cultural background, authorial intent, and so on — without feeding on the riches exegesis has revealed — we can starve spiritually. We have set the table and prepared the meal. In meditatio we enjoy the feast.