Introductory Note:

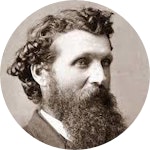

The nineteenth century naturalist John Muir remains one of my favorite loosely devotional writers. Muir offers beautiful portraits and exquisite tales from the “Book of Nature” -- God’s second great book.

I don’t offer this piece for its theological critique—in fact, I could take issue with some of the possible implications that could be drawn from this, and would hold to the belief that death is overcome through resurrection life in Christ. Where I do find this piece helpful, however, is in the bracing challenge it offers to a culture obsessed with youth and largely removed from death and dying. Through the years I’ve found myself returning to this article as it offers courage and beauty to face what so many of us fear — death.

This piece was written in 1867 while Muir spent a season sleeping in Bonaventure cemetery on his walk from Illinois to Florida. Bonaventure is located just outside of Charleston, South Carolina and would later be featured in the book and film Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil.

Nathan Foster

But of all the plants of these curious tree-gardens the most striking and characteristic is the so-called Long Moss (Tillandsia usneoides). It drapes all the branches from top to bottom, hanging in long silvery-gray skeins, reaching a length of not less than eight or ten feet, and when slowly waving in the wind they produce a solemn funereal effect singularly impressive.

There are also thousands of smaller trees and clustered bushes, covered almost from sight in the glorious brightness of their own light. The place is half surrounded by the salt marshes and islands of the river, their reeds and sedges making a delightful fringe. Many bald eagles roost among the trees along the side of the marsh. Their screams are heard every morning, joined with the noise of crows, and the songs of countless warblers, hidden deep in their dwellings of leafy bowers. Large flocks of butterflies, all kinds of happy insects, seem to be in a perfect fever of joy and sportive gladness. The whole place seems like a center of life. The dead do not reign there alone.

Bonaventure to me is one of the most impressive assemblages of animal and plant creatures I ever met. I was fresh from the Western prairies, the garden-like openings of Wisconsin, the Beech and Maple and Oak woods of Indiana and Kentucky, the dark mysterious Savannah Cypress forests; but never since I was allowed to walk the woods have I found so impressive a company of trees as the tillandsia-draped Oaks of Bonaventure.

I gazed awe-stricken as one new-arrived from another world. Bonaventure is called a graveyard, a town of the dead, but the few graves are powerless in such a depth of life. The rippling of living waters, the song of birds, the joyous confidence of flowers, the calm, undisturbable grandeur of the Oaks, mark this place of graves as one of the Lord’s most favored abodes of life and light.

On no subject are our ideas more warped and pitiable than on death. Instead of the sympathy, the friendly union, of life and death so apparent in Nature, we are taught that death is an accident, a deplorable punishment for the oldest sin, the arch-enemy of life, etc. Town children, especially, are steeped in this death-orthodoxy, for the natural beauties of death are seldom seen or taught in towns.

Of death among our own species, to say nothing of the thousand styles and modes of murder, our best memories, even among happy deaths, yield groans and tears, mingled with morbid exultation; burial companies, black in cloth and countenance; and, last of all, a black box burial in an ill-omened place, haunted by imaginary glooms and ghosts of every degree. Thus death becomes fearful, and the most notable and incredible thing heard around a death-bed is, “I fear not to die.”

But let children walk with Nature, let them see the beautiful blendings and communions of death and life, their joyous inseparable unity, as taught in woods and meadows, plains and mountains and streams of our blessed star, and they will learn that death is stingless indeed, and as beautiful as life, and that the grave has no victory, for it never fights. All is divine harmony.

Excerpted from John Muir’s A Thousand-Mile Walk to the Gulf, Chapter 4, “Camping Among the Tombs” (pp. 88 – 90).