The Problem of Virtue

Holiness has something of a bad press.

Being “holy” does not seem very desirable to many people in our contemporary society. Those who speak up for virtue are often derided as moralistic, sanctimonious, or holier-than-thou. The media reacts sharply against “preachy” public figures who presume to tell us how to order our private lives. And those who appear to be living lives of moral rectitude are treated with suspicion: can they really be whiter than white? Or are they hiding darker truths about themselves – clean on the outside, but as filthy as the rest within? We have seen so many spectacular falls from grace amongst our celebrities, politicians, and church leaders that we have become wary of taking virtue at face value. There are, it would seem, more wolves in sheep’s clothing than there are genuine sheep.

And who, after all, wants the sheep’s life anyway? Frankly, to many of us sin just seems a lot more fun than sainthood. Fans of The Simpsons know that, however flawed Homer and his family might be, they are a sight more bearable than the obnoxiously religious and impossibly perfect Ned Flanders. Just as the devil sometimes seems to have all the best music, so he often appears to have all the best and most entertaining pursuits, leaving the pious to their hair-shirts and homilies. It often looks as though the good and the godly are gingerly picking their way through a minefield of “thou shalt nots” while sinners romp in wide open meadows. Holiness only holds us back.

Or so it appears. But these images of sanctity and sin fall apart when we take a closer look at them. In fact, when we take the time to reflect on the nature of virtue and vice, we make the unexpected discovery that it is holiness that leads us into the fullest, most enriching experience of life, while sin acts like a malignant cancer, slowly tearing us apart from within. We are made to be holy. And Jesus offers us the most profound insights into holiness – not only in his teaching, but also in the vibrant quality of his deeply virtuous life.

Created to Love

The opening chapter of the Bible tells us that we are made “in the image of God” (Gen 1:27). Scholars and theologians have reflected for over two millennia about exactly what that might mean, but the apostle John, in his first letter, gives us an important insight into at least one significant implication. “God is love,” he writes, “and those who abide in love abide in God, and God abides in them” (1 Jn 4:16). To bear the character of God is to have love hardwired into our essential nature. The more we are conformed to the character of God, the more perfectly loving we will become. We are created to love.

When God calls us to holiness, he roots that call in his own character: “Be holy,” he says to the Israelites, “for I am holy” (Lev 11:44). Holiness, then, cannot simply be an abstract purity of our interior nature – an unsullied conscience, free from guilt. Rather it is a summons to pure love, to be the kind of people who can develop good, deep, loving relationships, both with God and with other people, relationships which are safe and enriching for all concerned. Jesus certainly seems to understand the call in this way. In the first half of the Sermon on the Mount he addresses a series of issues which threaten to undermine the quality of loving relationships: anger, adultery, divorce, deception, and revenge. He then pushes the boundaries of love further than any reasonable morality would seem to demand: “Love your enemies,” he says, “and pray for those who persecute you” (Mt 5:44). In this way, he says, you will “be perfect, as your heavenly Father is perfect” (Mt 5:48). Love, it seems, is the fulfillment of holiness.

Many years later, the great twelfth century Dominican writer Thomas Aquinas picked up on this strand of biblical teaching and made the startling assertion that love was more than the goal of Christian perfection: it is the fundamental power behind the created order. Just as physicists probe sub-atomic structure to identify the basic forces and particles that make up this physical universe, so Aquinas probed to the depths of Christian theology to identify the driving energy behind creation itself. In the end, Aquinas argued, everything is grounded in love, since all creation reflects the character of the one who made it. He suggested that we are not only made to love, we are made of love. Everything we do is driven by this divine quality: all we can do is love.

But Aquinas had no illusions about the terrifying human capacity for sin. He wrote about the lethal power of sin, that “turning away from our last end which is God.” He came to see love as having the kind of awesome power we see in nuclear fusion. Well-ordered and directed to the right ends, love can transform lives, inseparably unite people with one another and God, and act as the harmonious and creative power which holds all creation in being. But misdirected – allowed to turn in on itself, allowed to run wildly on the heels of any and every desire of our misguided hearts – love can become a horrifyingly destructive force, tearing apart the world from under our feet. Love, rightly ordered, will be the foundation of the kingdom of God. But grotesquely disordered love, inordinate self-love which swirls in on itself like a fierce tornado, has the capacity to shape tragedies like Auschwitz or the Rwandan genocide. Sin – love disordered is horrific. But holiness – love rightly ordered is life in all its abundance.

Love: The Holiness of Jesus

We see this reflected in almost every page of the Gospel narratives. The Pharisees were created to love, but they turned that love in on themselves and exalted themselves as the guardians and purest practitioners of piety. They took the gift of life embodied into the law and transformed it into an instrument of condemnation and death. Hence their disordered love could allow them to drag a woman into the presence of Jesus and demand that she be stoned to death (Jn 8:2 – 11) yet resist Jesus’ gift of liberating healing in the synagogue because it is offered on the Sabbath (Mk 3:1 – 6). More significantly, the inwardly-twisted self-love of all those in Jerusalem, Jews and Gentiles together, drove the authorities and crowds to brutalize Jesus before nailing him to a cross where he might hang in agony and die. The horror of sin is plain in story after story, and nowhere more so than at Golgotha.

Yet the well-ordered love of Jesus – his holiness – runs through the Gospel narratives like a refreshing river. Confronted with a demoniac in their midst, the Gerasenes had reacted with fear and loathing, dreading the danger to themselves. Seeing only the problem they reacted strongly, pushing the man from their midst: “he had often been restrained with shackles and chains … night and day among the tombs and on the mountains he was always howling” (Mk 5:4 – 5). But in his profound love, Jesus sees the man. Notice this: it is not the demons who are asked to name themselves; Jesus asks the man himself, “What is your name?” Treating the demons with contempt, he casts them out; treating the man with the kindest regard, he seeks to know him and draw near to him – perhaps the first person who has ever sought to do so.

Other examples of this profoundly well-ordered love abound. And fascinatingly those most damaged by sin, or most sickened by the sin within them, found this holiness not repellent but deeply attractive. There is no hint here of a judgmental “holiness” which defines itself over and above the flawed natures of others (the “holiness of the scribes and Pharisees” about which Jesus was so bitingly severe). In Jesus some of the most ruined souls found a refuge of love and grace. Mary Magdalene, in whom Christian tradition discerned a seriously disordered sexuality, found the one man with whom she could be safe. Levi and Zaccheus, both despised tax collectors, found one who refused to despise any. A man afflicted with leprosy found one person who was willing to reach out and touch him – perhaps as much a miraculous healing as the curing of his disease itself (Lk 5:12 – 16). A woman who was broken and weeping over her sinfulness found not only forgiveness, but one who defended her against her accusers (Lk 7:36 – 50).

This is the holiness to which we are called: a purity, certainly, but not a purity which stands aloof from a filthy and corrupted world, looking down with sanctimonious pity or judgmental horror on those still mired in vice. This is a purity of heart; a heart healed from the dreadful inward turn that maims its capacity to love well, a heart liberated from self-obsession, a heart enabled to do one thing only, and that thing well – to love. Jesus lived that purity, that holiness. And it is possible to learn from his life, teaching, and practices, how to open ourselves to the healing grace of God in such a way that this loving holiness is formed in our lives too. As we become like Jesus, we can become more truly holy … and rejoice in it!

Love Misdirected

Thomas Aquinas, in his Summa Theologiae, discusses the root and origin of sin by comparing two verses, one from the New Testament and the other from the Deuterocanonical books. He notes first that Paul writes to Timothy: “the love of money is a root of all kinds of evil” (1 Tim 6:10). But alongside this he sets a line from the apocryphal book of Sirach which says (in the Latin Vulgate), “pride is the beginning of all sin” (Sir 10:15). Whether or not we want to accept, with Aquinas, the authority of the deuterocanonical text, the point he makes from these verses fits well with the tenor of Scripture as a whole. The first, he says, describes the way in which we allow our hearts to turn to an inappropriate degree towards the beauty and richness of creation. But the second cuts to the deeper and more serious issue of the way we allow our eyes to be turned away from God himself in the first place. As Paul puts it so directly, “they exchanged the truth about God for a lie and worshiped and served the creature rather than the Creator” (Rom 1:25). Our hearts become increasingly holy as they are healed of these twin maladies; we begin though by focusing our attention on the latter, our prideful turning from God.

The most odious corruption of love within our souls takes place when we allow love to become inwardly directed and self-absorbed. Christians insist on a simple truth which is strikingly counter-cultural in our contemporary society, obsessed as it is with self-realization and self-regard: we are not here to love ourselves.

Now that needs some qualification, of course. It is not that we Christians are called to hate ourselves. The loathing which some people experience when they look in the mirror is neither natural nor healthy. But, contrary to the way many preachers and writers have come to interpret Christ’s teaching on the great commandments, the call to “love your neighbor as you love yourself ” (Mt 22:39) does not imply that our first task is to learn self-love.

The twelfth century Cistercian writer Bernard of Clairvaux had a clearer picture. In his short but brilliant work “On Loving God,” he argued that love at its least perfected is inwardly focused, seeking only its own good. And this self-love is not true love at all, merely the power of love corrupted into pride and vanity. As grace begins to reorder our hearts, though, some of that love starts to turn outward, towards God (and our neighbor), drawing us beyond ourselves – even if initially only because of the selfish benefits we can derive from others. A yet more well-ordered heart is able to love God and others for their own sake. And finally, says Bernard, we then truly learn what it means to love ourselves: to be grateful for the gift of ourselves, the only thing we truly have to offer to God and those around us, to express love. Growth in holiness ends in a proper love of self by turning outward to others, not by turning inward on ourselves.

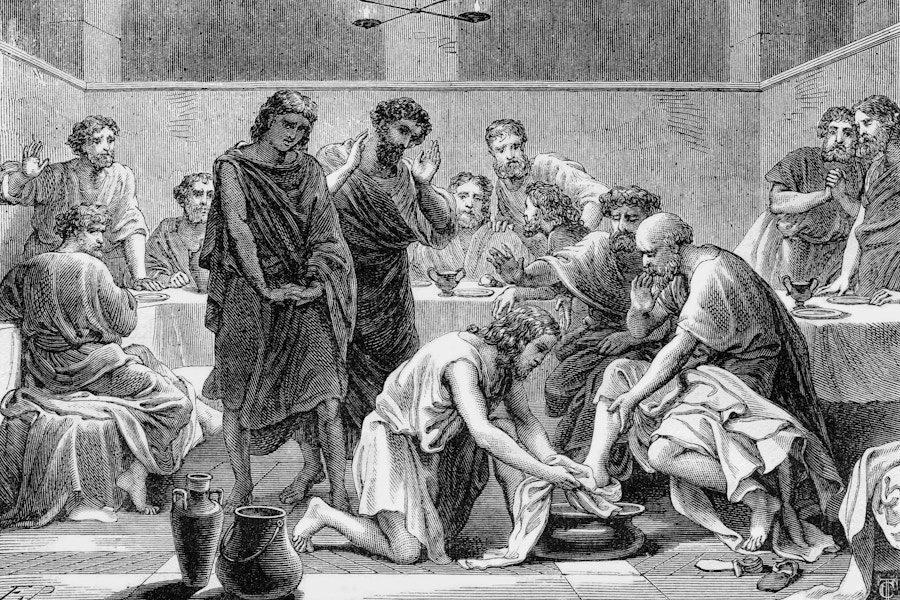

The hallmark of the holiness of Jesus is this constant turning toward others seen in his constant acts of humility and service. Perhaps the most striking example occurs on the night of the last supper. The apostle John tells us that Jesus, fully aware of his divine origins and significance, was seeking a way to love his disciples “to the end” (Jn 13:1 – an equally accurate translation of the Greek could be “to the utmost”). So he stripped off his outer garment and proceeded to perform the work of the lowest, most menial slave: washing the filthy, dirt-crusted feet of those around him. The disciples are shocked and appalled, so much so that Peter is embarrassed for Jesus and tries to refuse. But Jesus persists, teaching them what holiness towards others might mean – and calling them to love one another to exactly the same degree.

For we who follow Christ, opportunities for similar acts of humble service abound. The world around us scrambles to be the first, the greatest, the strongest; the way is wide open for those willing to become the least and the last. Jesus himself gives us numerous ideas of how we might live into the holiness of the servant. Choose to take the lowest place in the pecking order, not the highest (Lk 14:7 – 11). Share meals with outcasts, even inviting them into your home (Lk 14:12 – 14). Do not be misled by trappings of honor and power, but be ready to recognize the presence of the King of Glory in even the smallest child (Lk 9:46 – 48). You might want to stop reading for a moment and reflect. What opportunities has God placed before me to serve others? Do I sense the resistance of my heart to taking the lowest and least place? Pray for the grace to be able to lay aside pride and take up the servant’s towel. A heart reordered towards others is a heart which is growing in holiness.

Excessive Love

Continuing to analyze the effects of sin on the human heart, just as a doctor carefully diagnoses the sick patient, Aquinas turned from pride, the origin of sin, to the inappropriate love for creation which is the root of so many kinds of evil. Here is a love which at least looks beyond ourselves, he suggests – but which is nevertheless disordered, since it is not fully turned towards “our last end, which is God.” This is love which places the creation above the Creator.

Again it might help to clarify. Christians have always resisted the idea that material creation in itself is bad, evil, or corrupt. Genesis tells us repeatedly that as God called the various elements of creation into being, he “saw that it was good” (Gen 1:4, 10, 12, 18, 21, and 25). Human beings delighted him so fully that after their creation he went further, proclaiming the newly formed universe “very good” (Gen 1:31). There is certainly no grounds in Scripture for a religion that delights in the spiritual while denigrating the physical world. The dust from which the sons and daughters of God are made is both very physical and very wonderful.

But it is possible for us to delight in the material creation to an inordinate degree, in ways that are good neither for us, for others, or for the wider world – and which certainly draw us away from any depth of intimacy with God. Classically Christians have spoken of three cardinal sins which afflict us in this way: gluttony (an inordinate appetite for food), avarice (an unbalanced desire for wealth), and lust (a disordered love of sexual pleasure).

Once again it is Jesus who shows us not only what a profoundly well-ordered life looks like, in contrast to these degrading vices, but also the practices of life which make life-giving virtue and holiness possible.

Jesus enjoyed food and drink. He is often depicted in the Gospels sharing meals with people: with his disciples, with the “tax collectors and sinners,” and with Pharisees. He talked of the kingdom of God in terms of a great Messianic banquet. He accepted invitations to parties, and even helped along the celebrations at a wedding reception in Cana. In contrast to John the Baptist, who lived very austerely, Jesus acquired the reputation of being a “glutton and a wine bibber” (Mt 11:19)! Yet he kept his enjoyment within moderation; we have no indication that he ate or drank to excess. And he was able to use the gift of food to draw people deeper into their life in God; he used the feeding of the five thousand as the launching point for a conversation about the true “bread from heaven” (Jn 6:22 – 59), and instituted as the central act of Christian worship a common meal, the breaking of bread and sharing of a cup.

In the same way, Jesus was able to enjoy the material world around him while maintaining a life of deliberate simplicity. He was neither averse to wealth (some who followed him were people of considerable means, who supported his ministry and entertained him in their homes), nor hungry to acquire it. Like Paul, he had “learned to be content” with whatever he had (cf Phil 4:11).

It is more difficult for us to reflect on the well-ordered sexual desires of Jesus. For some, it may be difficult to consider the idea, although that probably has more to do with our disordered understanding of sexuality than with Jesus himself. Simply put, Jesus became human – fully human – and so became a sexual being, even if he never consummated that sexuality in a relationship. (As an aside, Dan Brown’s contention in The Da Vinci Code that the church might be rocked by a revelation that Jesus fathered children was simply nonsense – there was never any theological problem there, only the simple historical problem that it had never happened …!) Jesus was not some strange asexual being; he had a well-ordered sexuality which never sought to use other people simply for his own gratification. As the writer to the

Hebrews puts it, Jesus “in every respect has been tested as we are, yet without sin” (Heb 4:15).

One of the simple practices Jesus used to keep his appetites well-ordered seems to have been a cycle of fasting and feasting. The value of fasting for keeping our appetites in check is self-evident, and we certainly see Jesus practicing fasting at some of the most critical moments of his ministry. The spiritual discipline of feasting may seem less obviously helpful. It is essential, however, that we not only learn how to keep our physical desires in check, but also that we learn how to properly enjoy creation as a means of fostering our love for God and other people. As you read, you might want to reflect for a moment. Which of my appetites are most disordered? What effect does that have on me, and on others? How might I more appropriately use the gifts of food, money, and sexuality to express genuine, self-giving love for others? How can my relationship with creation become more celebratory, and less consumptive? Pray for the gift of greater holiness in your relationships with the material world around you.

Lukewarm Love

The last major barrier to holiness which our hearts face is the cooling of our ardor for God. The Christian tradition has often spoken of this as the sin of sloth, a translation of the Greek word akedia (sometimes written in its Latinate form, accidie). We tend to think of sloth as a very minor issue, little more than oversleeping on a sunny Saturday morning, or failing to file our tax returns on time. But for Christians that word has always had a much more pointed meaning: it is the failure to maintain an attentive and passionate love for God, a neglect of the greatest commandment: “love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your mind” (Mt 22:37).

The early Desert Christians of Egypt spoke of akedia in vivid and concrete terms as the “noonday demon.” Picture the monk in his cell, they would say. As the sun rises, so the monk rises filled with enthusiasm for the new day. Psalms are sung, and prayers are recited. The day’s work begins. Throughout the morning, the monk remains fervent and attentive to God. But as the burning sun rises high into the sky, time seems too slow. Energy levels drop. Evening seems so far away, and both work and prayer become unbearably tedious. The monk becomes listless and restless. The pursuit of God comes to an exhausted halt.

This is a beautiful metaphor of the Christian life as a whole, compressed into a single day. Following Christ is a long haul proposition. It is easy to begin with tremendous enthusiasm, only to find after a number of years that our piety has become a familiar habit, and our devotion rote. Church no longer inspires us. Our prayers and Bible readings are dutiful, but not life-changing. And at this point it is very easy to allow our white-hot passion for God to cool into a more comfortable glowing ember. It is easy to let love sleep.

Jesus refused to let his relationship with the Father slip into torpidity. It’s instructive to see how he nurtured the fire of love – there is much we can learn here from our Master and Teacher. We discussed Jesus’ life of prayer in the previous issue of Explorations; clearly the time Jesus spent in prayer, in silence, in contemplative attentiveness to his Father helped greatly to nurture the intimacy of that relationship. We also notice in the Gospels that Jesus is very attentive to the life of public worship of his community. Luke tells us that attending his synagogue on the sabbath “was his custom” (Lk 4:16). As far as we can tell, he made the pilgrimage to Jerusalem for the great feasts of Passover, Tabernacles, and Pentecost every year of his public ministry – a pattern of worship he had learned during his upbringing. And he spent time on “retreat” – withdrawn from the bustle of his public life, finding time to seek his Father’s face in solitude. Here the Contemplative and Holiness traditions fuse. A prayer-filled life lays foundations for virtue, which in turn enables our soul to experience ever greater intimacy with God.

You may want to pause here again for a few moments and reflect. The Song of Songs tells us that “love is strong as death, passion fierce as the grave” (7:6). Is that the kind of love you are experiencing for God? If so, how can you best fuel and express that passion? If not, how might you recapture an ardent love? Do you need to arrange a retreat, or some time for prayer and silence? How might your church be able to help? Pray for a renewed fire of love, and for the wisdom to know how to fan it to flame rather than smother it.

Integrated Love: Life Ordered to a Single End

The English word “holiness” is drawn from an older word meaning “wholeness.” The wholeness God desires for us happens as the various desires and disorders of our souls are healed and united towards a single end: love. As God’s grace draws us into an ever fuller life of sacrificial, self-giving love we increasingly become the people we were created to be, people who fully reflect the essential character of God. Perfect holiness is perfect love, and this is the goal towards which Jesus continually beckons us, no matter how frequently we fall short. As we live into the way of Christ, our twisted self-love is slowly straightened out, our excessive love for creation is brought into appropriate proportion, and our lukewarm love for God is kindled into burning fire. The practice of virtue leads to integrity, to an integration of our scattered souls into one unified whole. We discover the wonderful pleasure of holiness.

C. S. Lewis once wrote: “We are half-hearted creatures, fooling about with drink and sex and ambition when infinite joy is offered us.” Jesus shows us how to embrace a life that is abundant and full, a life of integrity and wholeness, a life surrendered to love. This is the way of holiness; Christ invites you to walk in it.

From the Renovaré Explorations newsletter archives.

Text First Published December 2009